“Una Storia” e “Manuale per gli amici profughi” di Li Young-Lee # Traduzione di Federico Leoni

“Una Storia” e “Manuale per gli amici profughi” sono due poesie inedite di Li Young-Lee tradotte per noi da Federico Leoni.

Una storia* di Li Young-Lee

Triste colui che non sa raccontare

quando gli viene chiesta una storia.

Suo figlio ha cinque anni, aspetta, siede in grembo.

Non la solita storia, papà, una nuova.

L’uomo si gratta il mento, l’orecchio.

In una stanza zeppa di libri, in un mondo

fatto di storie, non ne ricorda alcuna:

Presto il ragazzo ne avrà abbastanza,

pensa, di suo padre.

La mente dell’uomo corre già al giorno

in cui suo figlio se ne andrà. Non farlo!

Ecco la storia dell’alligatore, dell’angelo!

Quella del ragno, quella che ami e ti diverte.

Lasciami raccontare!

Ma il ragazzo già piega i suoi vestiti,

già cerca le chiavi. Sei forse un dio,

urla l’uomo, ché davanti ti siedo muto?

Se sono un dio farei bene a non deluderti.

Ma il ragazzo è ancora lì. Dai papà, una storia.

È un’equazione sentimentale più che logica,

assai più celeste che terrena.

Somma l’amore di un padre alle richieste

di un figlio: non otterrai che silenzio.

*tratta da The City in Which I Love You, BOA Editions Ltd.

A story di Li Young-Lee

Sad is the man who is asked for a story

and can’t come up with one.

His five-year-old son waits in his lap.

Not the same story, Baba. A new one.

The man rubs his chin, scratches his ear.

In a room full of books in a world

of stories, he can recall

not one, and soon, he thinks, the boy

will give up on his father.

Already the man lives far ahead, he sees

the day this boy will go. Don’t go!

Hear the alligator story! The angel story once more!

You love the spider story. You laugh at the spider.

Let me tell it!

But the boy is packing his shirts,

he is looking for his keys. Are you a god,

the man screams, that I sit mute before you?

Am I a god that I should never disappoint?

But the boy is here. Please, Baba, a story?

It is an emotional rather than logical equation,

an earthly rather than heavenly one,

which posits that a boy’s supplications

and a father’s love add up to silence.

Manuale per gli amici profughi* di Li Young-Lee

Se il tuo è un paese dove le campane/suonano a festa,/per annunciare il cambio di stagione/o la venuta al mondo di demoni e di dei,/allora farai meglio a vestire sobriamente/quando arrivi negli Stati Uniti,/e a non parlare a voce troppo alta./

Se hai visto uomini armati/pestare tuo padre e trascinarlo via/oltre la porta di casa/ e fino al baule di un furgone acceso,/se allora tua madre ti ha strappato dalla soglia/soffocandoti nelle pieghe della gonna,/non giudicarla troppo duramente./Non chiederle cosa pensasse di fare/quando ha distolto lo sguardo del figlio/dalla storia, per volgerlo al luogo in cui hanno inizio/ le pene dell’uomo./

E se incontri qualcuno/nel paese che ti ha accolto/e credi di vedere nel suo volto/un cielo aperto, una nuova speranza/forse sei ancora troppo lontano./

Troppo vicino, forse, se pensi di leggere negli altri,/ come si legge in un libro senza inizio né fine,/la storia del tuo paese natale,/paese cancellato due volte,/dal fuoco la prima e la seconda dall’oblio./

In ogni caso cerca di non caricare sulle spalle degli altri/il peso delle tue speranze, della tua nostalgia./

E se, come alcuni,/ hai due volti diversi sulla stessa faccia/questo forse è un indizio./Guardare altrove è l’abitudine/che servì ai tuoi antenati per salvarsi./ Non lamentarti se non sei bello./Abituati a non guardare, vedendo./Impegnati a ricordare dimenticando./Muori e resta vivo e sogna di finirla./

Elaborati almanacchi e mappe/di sistemi solari remoti/ornavano probabilmente le campane/create dai tuoi antenati in varie fogge,/nessuna indicazione, tuttavia,/per la diaspora di pronipoti erranti./

Scommetto che non sai in quale lingua/tuo padre urlò a tua madre/dal retro del furgone: “lascialo guardare!”/

Forse non era la lingua che usavi ogni giorno in casa./Forse era una lingua dimenticata./Forse c’era troppo chiasso, urla e pianti,/e il frastuono delle armi per la strada./

Ma non importa. Ciò che conta/è che il regno dei cieli è buona cosa/ma il paradiso in terra è ancora meglio./

Pensare è bene,/ma ancora meglio è vivere./

Bello starsene seduto/a leggere un buon libro./L’amore, però, è ancora meglio.

*tratta da Behind My Eyes, W.W. Norton, 2008

If your name

suggests a country where bells

might have been used for entertainment,

or to announce

the entrances and exits of the seasons

and the birthdays of gods and demons,

it’s probably best to dress in plain clothes

when you arrive in the United States.

And try not to talk too loud.

If you happen to have watched armed men

beat and drag your father

out the front door of your house

and into the back of an idling truck,

before your mother jerked you from the threshold

and buried your face in her skirt folds,

try not to judge your mother

too harshly. Don’t ask her

what she thought she was doing,

turning a child’s eyes away

from history

and toward that place all human aching starts.

And if, one day, you meet someone

in your adopted country and believe

you see in the other’s face an open sky,

some promise of a new beginning,

it probably means

you’re standing too far away.

Or if you think you read

in the other, as in a book

whose first and last pages are missing,

the story of your own birthplace, a country twice erased,

once by fire, once by forgetfulness,

it probably means you’re standing too close.

In any case, try

not to let another carry

the burden of your own nostalgia or hope.

And if you’re one of those

whose left side of the face doesn’t match

the right, it might be a clue

looking the other way was a habit

your predecessors found useful for survival.

Don’t lament

not being beautiful.

Get used to seeing while not seeing.

Get busy remembering

while forgetting. Dying to live

while not wanting to go on.

Very likely, your ancestors decorated their bells

of every shape and size

with elaborate calendars and diagrams

of distant star systems,

but no maps

for scattered descendants.

And I bet you can’t say

what language your father spoke

when he shouted to your mother

from the back of the truck, “Let the boy see!”

Maybe it wasn’t the language you used at home.

Maybe it was a forbidden language.

Or maybe there was too much screaming

and weeping

and the noise of guns in the streets.

It doesn’t matter.

What matters is this:

The kingdom of heaven is good.

But heaven on earth is better.

Thinking is good.

But living is better.

Alone

in your favorite chair

with a book you enjoy

is fine. But spooning

is even better.

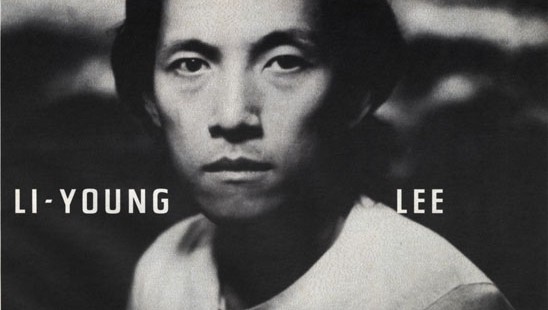

Li Young-Lee è nato a Giacarta nel 1957, da genitori cinesi. Il padre e la madre, costretti all’esilio per la loro opposizione al regime comunista, si trasferirono in Indonesia per poi spostarsi negli Stati Uniti, nel 1964. Li Young-Lee è vissuto prima a Seattle e poi a Pittsburgh, dove è diventato ministro del culto presbiteriano. La sua poesia, mistica ed elegiaca, unisce culture lontane ed è influenzata da autori cinesi come Li Bo e Tu Fu: parla di solitudine e malinconia, di una patria lontana o addirittura immaginaria, della bellezza come dono inaspettato e improvviso.

Li Young-Lee pubblicato quattro raccolte poetiche: Rose (1986), The City in Which I Love You (1990), Book of My Nights (2001) e Behind My Eyes (2009).

[…] Li-Young Lee, uno dei miei preferiti. Altre due delle sue poesie, inedite in Italia, sono sul blog Patria Letteratura, sempre tradotte da […]